This fall, I hosted an artist who participated in the 6th Annual Grand Canyon Celebration of Art. These days, he’s a renowned impressionist whose paintings are more valuable than most cars I’ve owned. But before he was painting fine art, he had a job drawing cartoon maps. I suppose that’s why I was primed to pay extra attention when I recently stumbled upon a couple of early-20th-Century cartoon maps of Grand Canyon.

These maps are an interesting contrast to one another. One is drawn by Jo Mora, whose legacy is well-summarized by the subtitle of a 1994 biography: Renaissance Man of the West. (You may already have seen his artwork on the cover of this album by the Byrds.) The other is drawn by a commercial artist named Jolly Lindgren, a man without a Wikipedia article.

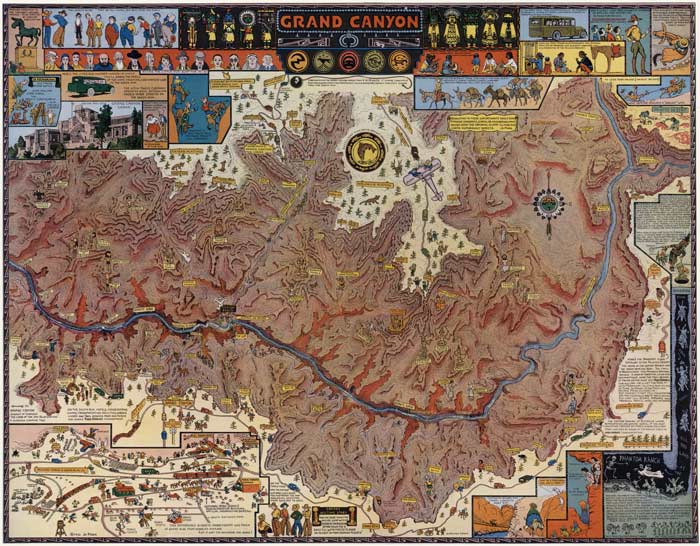

Here are the two maps, side by side. Mora’s, the first of the two, is by far the more lavishly illustrated of the pair.

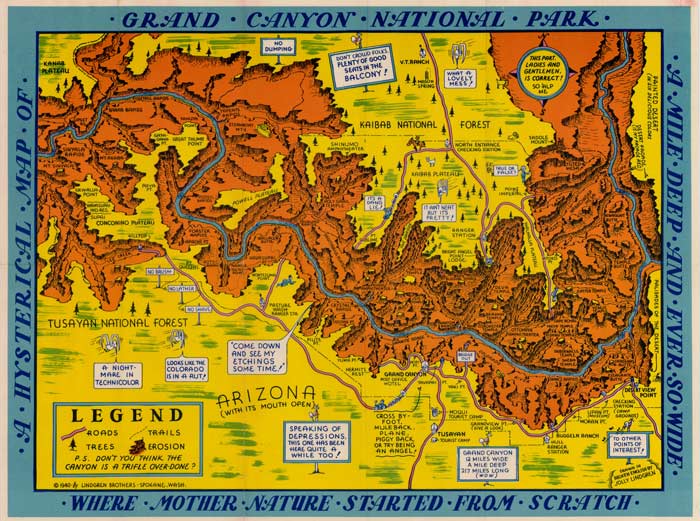

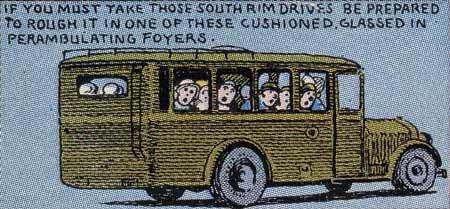

Lindgren’s map, however, seems “commercial” for its economy of linework — it seems to reflect an artist on a deadline. It is sparse on details and heavy on puns compared to Mora’s map.

Mora not only illustrated Western scenes, he photographed, painted, sculpted, and wrote about them. When his biographer calls him a renaissance man, he’s not exaggerating. Mora knew his subject matter. A quarter century before he drew his Grand Canyon map, Mora lived with Hopi and Navajo people near Grand Canyon for about two years.

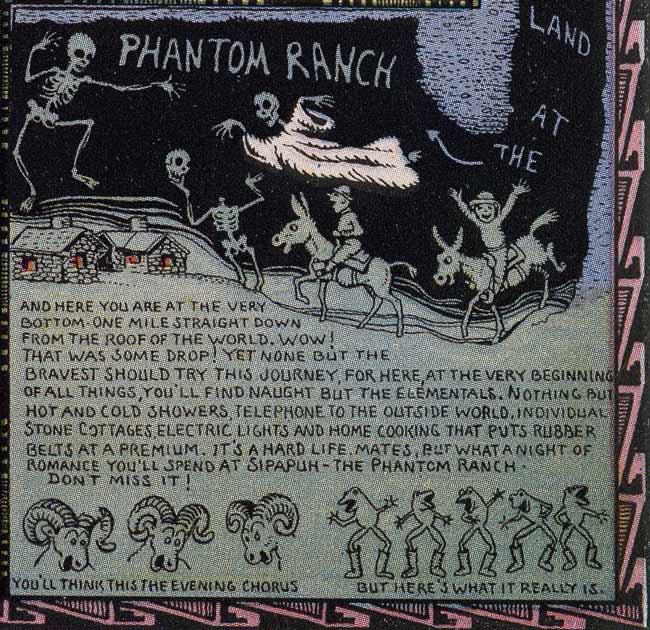

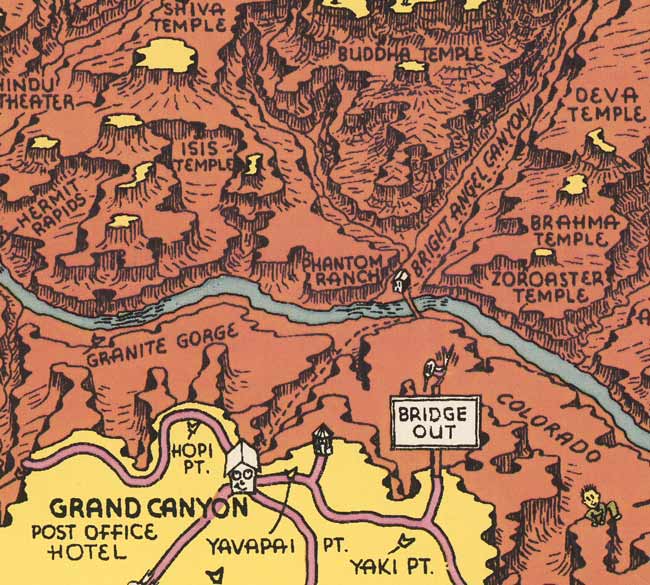

That extended residence makes one aspect of Mora’s map especially disappointing. Mora places Sipapu (here spelled “Sipapuh”), the Hopi point of emergence into this world, at Phantom Ranch. Every source that I am familiar with places this sacred spot along the Little Colorado River, not far from its confluence with the mainstem Colorado. Mora’s decision to conflate Phantom Ranch with Sipapu seems calculated to exploit one-dimensional Anglo-American beliefs about Native culture.

The obvious jokes at the expense of tourists are a surprising aspect of this map. At the bottom of the Phantom Ranch panel, Mora makes fun of visitors likely to mistake the sound of frogs for bighorn sheep. His description of the amenities at Phantom Ranch suggest a belief that not only do tourists suffer from cognitive dissonance, they actually embrace it: “Nothing but hot and cold showers, telephone to the outside world, individual stone cottages, electric lights and home cooking.” In other words: “Come rough it in luxury.” Glamping before glamping was a thing.

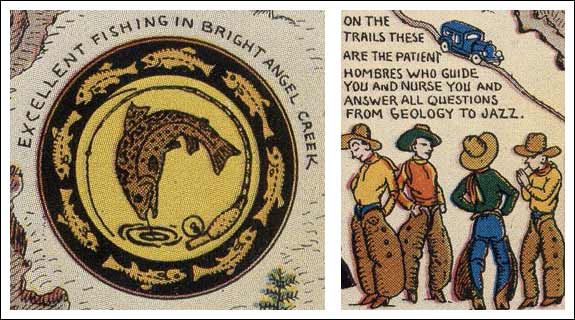

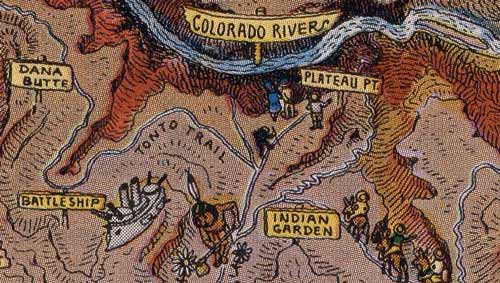

There are a couple other details on Mora’s map that jumped out at me: Non-native trout in Bright Angel Creek are held in high esteem. Guides are depicted as “patient hombres” who “answer all questions from geology to jazz.” And the circa-1930 trail network is depicted more-or-less-accurately throughout the South Rim area. Some of the trails that Mora depicts have since been abandoned, such as a spur trail that juts off to the west of Plateau Point. That same spur trail appears on USGS topographic maps from the era.

Right: Trail guides.

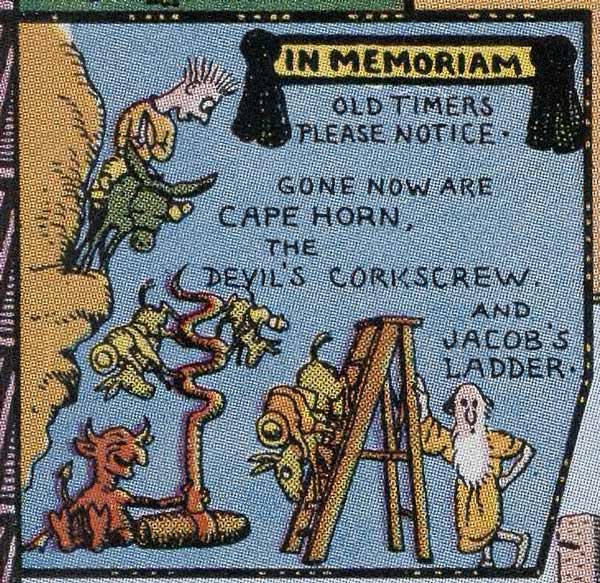

Like any piece of art, Mora’s map is a product of its time. The park’s south entrance road extends to Route 66, now supplanted by Interstate 40. Recent changes in land ownership are reflected in a drawing that eulogizes retired sections of trail. “Old timers” are advised that Cape Horn, Jacob’s Ladder, and Devil’s Corkscrew are all gone.

To better understand the significance of the eulogized landmarks, a little background is in order. Before Grand Canyon National Park was established, the Bright Angel Trail was known as the Cameron Trail, and it was operated as a private “toll road” under the control of Ralph Cameron. After the park was established in 1919, the trail corridor remained a private inholding until 1928. Upon obtaining Cameron’s land in 1928, the Park Service abolished the toll and rebuilt much of the trail.

From a modern standpoint, Mora’s eulogy may appear perplexing: The toponyms Jacob’s Ladder and Devil’s Corkscrew are still in use today. Hikers use them in reference to sections of the trail running through the Redwall Limestone and Vishnu Basement Rocks, respectively. But modern hikers are using those phrases in reference to a re-routed trail. The original Devil’s Corkscrew is long-abandoned, and I suspect the original Jacob’s Ladder was destroyed when trail crews blasted a new route through the Redwall. And nobody today talks about “Cape Horn.”

The other old cartoon map I came across, was drawn in 1940 by Jolly Lindgren and published by the Lindgren Brothers printing company. It bills itself as “A Hysterical Map of Grand Canyon National Park.” It’s a wonderful piece of work. I’m especially fond of the lettering.

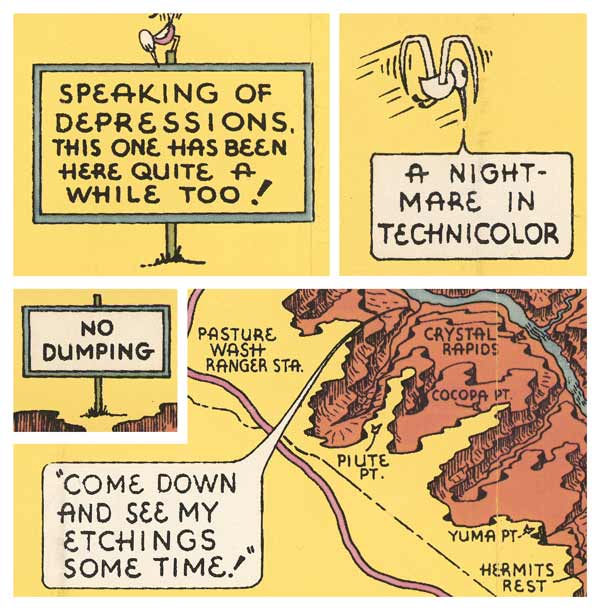

Some of the jokes are quite obviously a product of their time. For example: “Speaking of depressions, this one has been here quite a while too!” In 1940, the depression of the 1930s had yet to give way to the booming wartime economy. Elsewhere on the map, a passing bird declares the canyon “a nightmare in technicolor.” And a series of sequential roadside signs parodies Burma-Shave ads of that era.

The line “Come down and see my etchings some time!” is a mildly ribald double entendre. It references a phrase that, according to Wikipedia, “is a romantic euphemism by which a person entices someone to come back to their place with an offer to look at something artistic, but with ulterior motives.” Not that it’s unknown today, but I suspect the “etchings” euphemism was more commonplace in 1940.

One of the jokes reminds me of a Far Side cartoon published several decades after the map was printed. The map and the Far Side cartoon both show a “No Dumping” sign on the edge of the Grand Canyon.

Other jokes have me completely baffled. “True or False?” asks a hat-wearing man. “It’s a dang lie!” proclaims a motorist en route to Point Sublime. I simply don’t get it. Perhaps there’s some historic context I’m missing?

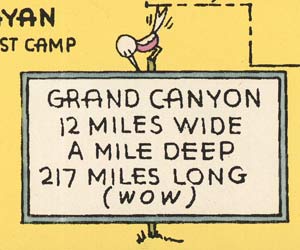

At least one fact presented in Lindgren’s seems to contradict modern information sources. The map asserts that the canyon is 217 miles long; today, the National Park Service gives the length of the canyon as 277 river miles.

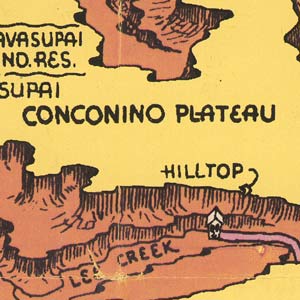

So who’s correct? Both are — for their time. When the map was published in 1940, the boundaries of Grand Canyon National Park did not encompass Marble Canyon, which stretches from Lees Ferry to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. The length of the canyon, then, was considered to be the number of river miles between the confluence and the Grand Wash Cliffs. In 1975, the park boundary was expanded to encompass all of Marble Canyon. Since 1975, Lees Ferry has been considered the official start of Grand Canyon. When Marble Canyon was designated part of Grand Canyon National Park, the canyon “grew” by some sixty miles.

I’ve had a difficult time finding much information about the Lindgren brothers. Jolly Lindgren’s life is summarized in a short obituary from 1952. According to his obituary, Lindgren served in World War I, founded his printing company with brother Oscar in 1928, and saw his “hysterical” maps achieve prominence in the 1930s. The business is described in more detail in a newspaper article from 1948, in which the reporter observes “the manufacturing of souvenir decals is a relatively new industry.” Jolly Lindgren’s obituary notes that “vacationing Spokanites have traveled thousands of miles to purchase a ‘made in Spokane’ decal to brighten an auto window.”

If you’d like to view larger versions of the maps — and some details from the maps — check out the Flickr gallery that I’ve assembled.

Great post, Mike! I am constantly amazed by your sleuthing skills and love your commentary. I shared this on my Facebook page because I think any Grand Canyon fan would be fascinated by these. Keep it up!!

Thanks, Denise! You might appreciate this quick addendum to the “217-mile problem.” After I wrote this post, I found a related post on Jeff Ingram’s excellent blog. Apparently, there was a sign at Mather Point that told visitors the canyon was 217 miles long. That sign stayed there until the 1970s.

On the basis of what Jeff writes, and what I have read elsewhere, it seems to me that the 217-mile figure was kept in circulation (at least in part) because it was a convenient fiction for dam builders. If they could claim with a straight face that Marble was not part of the Grand, then they could claim that there would be no dams in Grand Canyon.

Here’s the link to Jeff’s post:

http://gcfutures.blogspot.com/2012/04/on-edge-xiii-maps-are-meaningful.html

Amazing and sad to think that the Park Service had the map in the park so late with such misleading information. It is still frightening when I see the bore holes for the dam sites in the Canyon to this very day and know how fragile that protection is–very evident in the development still trying to sandwich either end and so close to actually happening.

Well said. (And a good reminder that I still need to read Encounters with the Archdruid by John McPhee! The book recounts a boat trip through Grand Canyon with David Brower and Floyd Dominy, then head of the Bureau of Reclamation.)