This post is the second half of a two-part series on early Grand Canyon Maps. It describes maps that were created as a result of US expeditions and surveys through 1903. An earlier post described maps that predate US Government exploration of Grand Canyon.

In a short history of Grand Canyon cartography, the Library of Congress explains why the maps offer so very little detail about the area:

The scarcity of data obtained by direct observation and documentation explains why very few early European maps provide much useful information about the region. For the most part, these early maps were compilations of information derived from the work or imagination of others.

The region remained largely unknown until the mid-to-late 1800s.

In 1848, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, ending the Mexican-American War. Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico ceded roughly half-a-million square miles of land to the United States. Grand Canyon was included along with most of the present-day Southwest. Westward ambitions required that the new United States territory be explored and mapped.

One of the first exploratory expeditions was that of Lieutenant Joseph Christmas Ives. The expedition followed the Colorado River from the Gulf of California northward until it reached unnavigable waters in Black Canyon, near the site where Hoover Dam is now situated. The expedition then backtracked downstream and continued overland to the east.

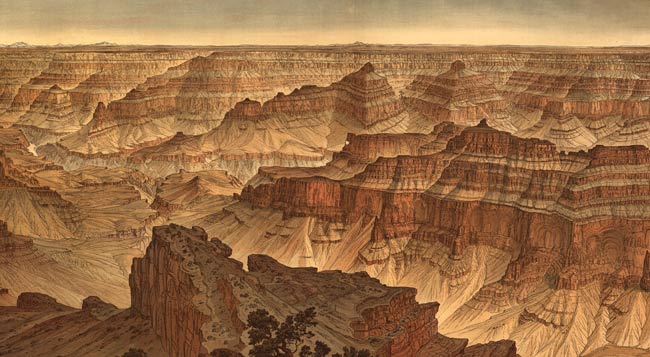

The expedition resulted in several remarkable creations. Expedition cartographer Baron Frederick Wilhelm von Egloffstein created a beautiful, modern-looking map of Grand Canyon — the first shaded relief map of the American West. John Strong Newberry produced the first formal study of Grand Canyon geology. And Lieutenant Ives produced a 450-page report mostly remembered for a single pessimistic assertion: “Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.”

Egloffstein’s map is lauded today for its realistic representation of Grand Canyon’s complex topography — it is unlike any map that preceded it, and it is important from both a historical and technical standpoint. In the final report on his expedition, Ives devotes his final appendix to a discussion of Egloffstein’s work and methods. Ives explains how Egloffstein endeavored to give his map the appearance of “a small plaster model of the country,” and he asserts that

This style … is, in beauty and effectiveness, much superior to the old … This method of representing topography is less conventional than the other [i.e., shadow hachures, an earlier technique], and truer to nature. It is an approximation to a bird’s eye view, and is intelligible to every eye.

Ives gave only a terse explanation of Eggloffstein’s printing method. Historian Imre Demhardt describes it as an innovative and now lost method that was held in secret.

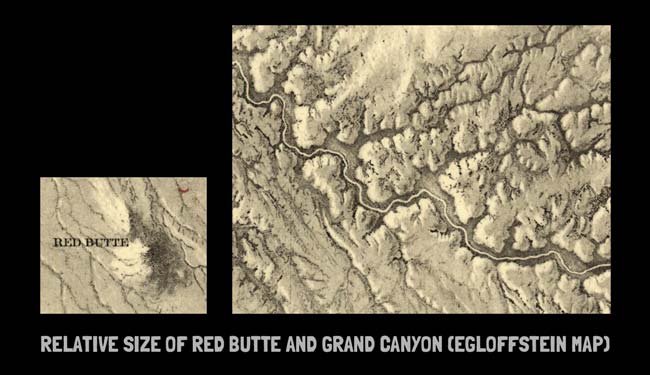

The expedition’s course is plotted on Egloffstein’s map, and its overland route is reflected in his depiction of Grand Canyon. Marble Canyon (which he presumably did not see) is absent. West Grand Canyon, where he traveled from rim to river, appears to be mapped in greater detail than areas farther east. Features that rose above the plateau on which he traveled seem to have been given disproportionate prominence — Red Butte, which is relatively small, appears enormous. It can be difficult to discern exactly where the canyon rim is supposed to lie, especially on the eastern half of the map.

The Egloffstein map doesn’t get everything right, but it is a massive leap forward compared to its predecessors. Its publication marked the beginning of an ever-improving series of maps that spanned the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Although he is remembered as an explorer and not a mapmaker, John Wesley Powell was responsible for some of the next great strides in Grand Canyon cartography. In 1869, John Wesley Powell led an expedition that successfully ran the Colorado River through Grand Canyon. Near the outset of the trip, many miles before they ever reached Grand Canyon, one of the boats was destroyed. This was very nearly disastrous for the expedition, in part because the wrecked boat carried barometers essential for measuring elevation. Thankfully, two of Powell’s men were able to reach the wrecked boat and recover not only the barometers but also a keg of whiskey.

Powell’s account of the journey describes how he and another man used the barometers to measure the heights of cliffs:

Howland and I determine to climb out, and start up a lateral canyon, taking a barometer with us for the purpose of measuring the thickness of the strata over which we pass. The readings of the barometer below are recorded every half hour and our observations must be simultaneous. Where the beds which we desire to measure are very thick, we must climb with the utmost speed to reach their summits in time ; where the beds are thinner, we must wait for the moment to arrive ; and so, by hard and easy stages, we make our way to the top of the canyon wall and reach the plateau above about two o’ clock.

In another more humorous passage, Powell describes an unproductive use of the sextant:

While eating supper we very naturally speak of better fare, as musty bread and spoiled bacon are not palatable. Soon I see Hawkins down by the boat taking up the sextant—rather a strange proceeding for him—and I question him concerning it. He replies that he is trying to find the latitude and longitude of the nearest pie.

Although the 1869 expedition was ostensibly mounted for scientific purposes, it is principally celebrated for Powell’s completion of the journey — a tremendous achievement in and of itself. Powell would travel a portion of the Colorado River through Grand Canyon on a second expedition in 1871-1872, attempting to better survey the region. Unlike the first Powell expedition, which was privately sponsored, the second Powell expedition was funded by a Congressional appropriation.

Congress continued to fund Powell’s survey work in the West throughout most of the decade. The Powell Survey was one of several ongoing, competing surveys that Congress funded during the 1870s.

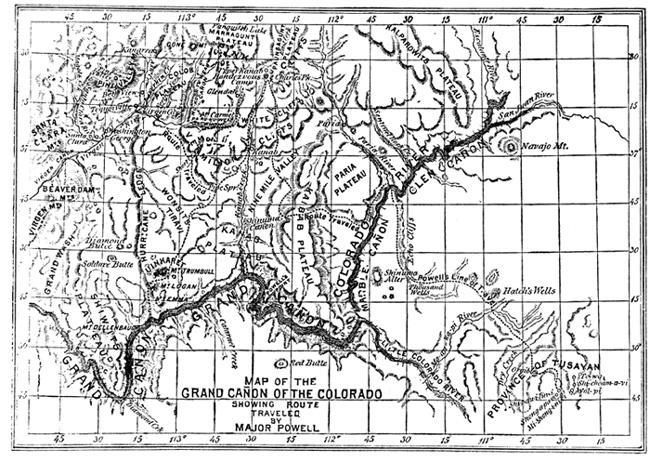

Powell himself produced only one map of the Grand Canyon area — it accompanied his written account of canyon adventures that appeared in a popular magazine — but he gathered the raw data necessary for the creation of many later maps. In fact, some of Powell’s later survey work superseded original, inaccurate work his expedition had performed within Grand Canyon.

Two of Powell’s contemporaries also produced noteworthy work: Clarence Dutton and George M. Wheeler.

Wheeler led his own eponymous military survey of the West, and helped to better establish the exact course of the Colorado River through Grand Canyon. Like the Ives Expedition, Wheeler proceeded upriver through Grand Canyon, going as far as Diamond Creek. Dutton, who accompanied Powell on his second Grand Canyon expedition, authored The Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, which contains drawings and maps of the Grand Canyon area. The book is considered a classic today. Writer Wallace Stegner describes Dutton as “almost as much the genius loci of the Grand Canyon as [John] Muir is of Yosemite.”

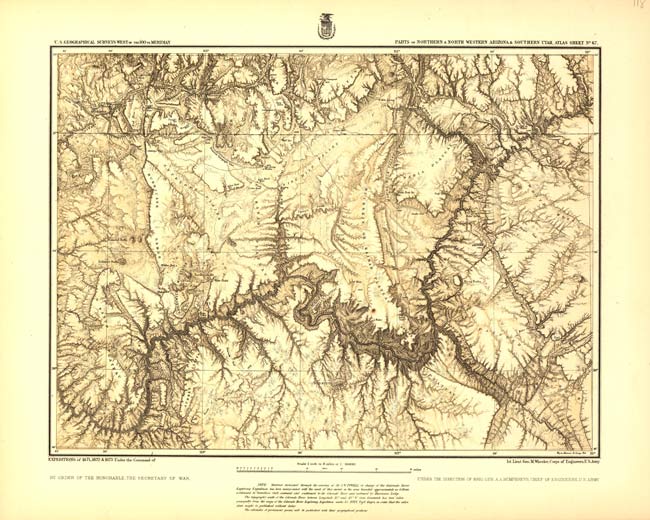

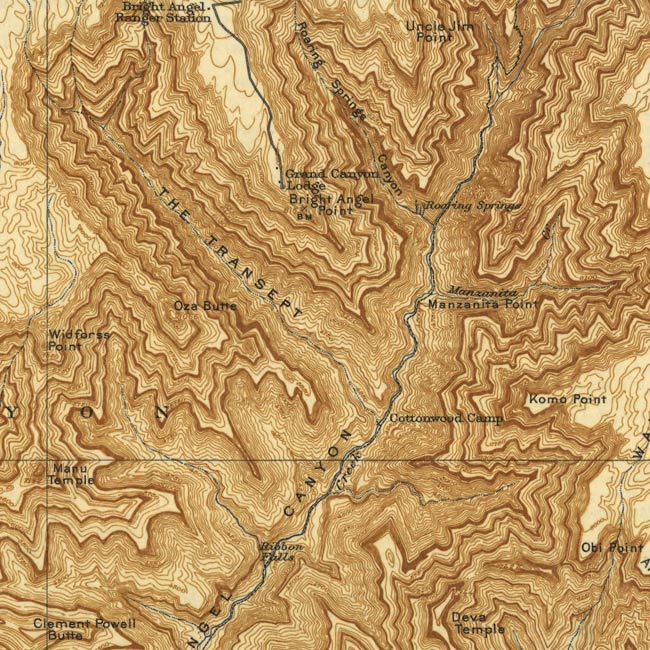

As the 1870s drew to a close, Congress ended the multiple ongoing surveys and consolidated mapping efforts within the newly created US Geological Survey (USGS). By 1886, the USGS had created its first topographic maps of Grand Canyon, based mostly on data from the Powell Survey. These are the first Grand Canyon maps that resemble today’s USGS topo quads. If you’re familiar with Grand Canyon geography, you can identify landmarks like Bright Angel Canyon, Great Thumb Mesa, and Powell Plateau, although various features appear distorted or misshapen.

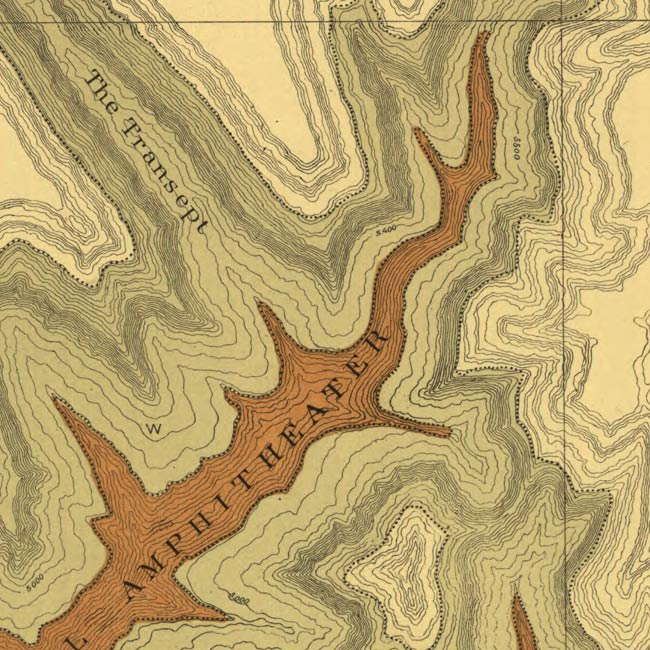

One of the best-known Grand Canyon maps is that of Francois Matthes. In 1902, the USGS tasked Matthes with producing a topographic map of Grand Canyon. Matthes’ resulting work, completed in 1903, was a great improvement over the previous generation of government maps. His survey resulted in a beautifully rendered technical achievement, and it would remain in widespread use for more than half a century.

A comparison of the 1886 and 1903 maps reveals what appears to be a proliferation of toponyms. However, not all of the newly appearing place-names were freshly coined. The 1886 maps are printed at 1/250,000 scale; maps based on Matthes’ 1903 survey are printed at 1/48,000 scale. The contour interval has been similarly reduced, from a cliff-swallowing 250 feet to a mere 50 feet. Obviously, there is room for more detail. Monument Creek, named by Powell in 1883, waited for Matthes before making an appearance on the map.

But that’s not to say the Matthes map doesn’t include any newly named features. Hermit Creek, for example, is named after Louis Boucher, the “hermit” who arrived at the canyon sometime between the creation of the two maps. Pipe Creek, near Indian Gardens, was named after a hoax that took place in 1894. The Matthes map illustrates more than just improved survey data, it records the naming of Grand Canyon features and its ever-more-intensive human use.

Over the years, the Matthes map underwent minor revisions to reflect changes like new roads, buildings, and place names. Various printings of the 1903 map show decades of South Rim development — the map was reprinted as late as 1960. The newer maps also eliminated trails that were no longer used.

A 1909 printing shows no roads or trails out to Pima, Mohave, Yaki, or Shoshone points. The map shows a somewhat extensive inner-canyon trail network, but South Kaibab and Hermit Trails had yet to be constructed. The predecessor to the modern Bright Angel Trail is shown, but it follows a routing that is slightly different from today’s trail. Then technically a “toll road” under the private ownership of Ralph Cameron, the 1909 printing refers to it as the Cameron Trail. In the Horn Creek area and elsewhere, the map shows routes that branch off the Tonto Trail and end at the Colorado River.

In later printings, the Cameron Trail would be renamed the Bright Angel Trail, and those Tonto-to-Colorado-River routes would disappear. The road to Hermits Rest eventually appears on the map, as does a monument to John Wesley Powell. Ninetyfour-Mile Creek, one of many natural features named after river distances during the 1923 Birdseye Expedition, remains unlabeled on maps that precede the survey.

Of course, there have been many other maps produced since then — everything from high-tech GIS projects to low-tech, cheaply printed handouts for tourists. It’s impossible to list every map that covers Grand Canyon, and this post stops short of covering the many important maps produced during the twentieth century. If you have any thoughts, questions, or corrections, I would love to hear them. Leave me a comment at the bottom of this post, and I’ll get back to you.

Additional reading

Library of Congress: Maps of Grand Canyon National Park (essay)

Library of Congress: Before Lewis and Clark

Codex 99: The Grand Canyon ‧ Part I – The Colorado River Maps – 1858+

Codex 99: The Grand Canyon ‧ Part II – The Bright Angel Maps – 1903+

Great article

Thanks, Dave! Glad you liked it.

Wonderful set of articles, thanks very much. I’m a Canyon addict and a map addict, so it’s no surprise that I read every word. I used some of those old Francois Matthes maps when I first started hiking the Canyon I the early 70’s!

George, thanks for the thoughtful comment! They’re beautiful maps, and it’s interesting to hear that they were used as late as the ’70s. I can imagine they would still be practical maps for many circumstances today.

This is all very interesting. Who is the author of this article?