This is the first in a two-part series about historic Grand Canyon maps. This post covers the Spanish colonial era and early 19th century. The second half, covering 19th-century American cartographic efforts including those of the Powell and Matthes Surveys, will be posted later this week.

One oft-repeated Grand Canyon story is that of Spanish explorer García López de Cárdenas’ expedition, whose members were the first Europeans to see the canyon. From his vantage point on the rim, Cárdenas mistakenly believed the river to be six feet wide — about fifty times short of its actual dimensions. His party’s attempts to cross the canyon ended in abject failure; after three days they had descended only a third of the canyon. In unmapped territory, Cárdenas was oblivious to the true scale of the canyon.

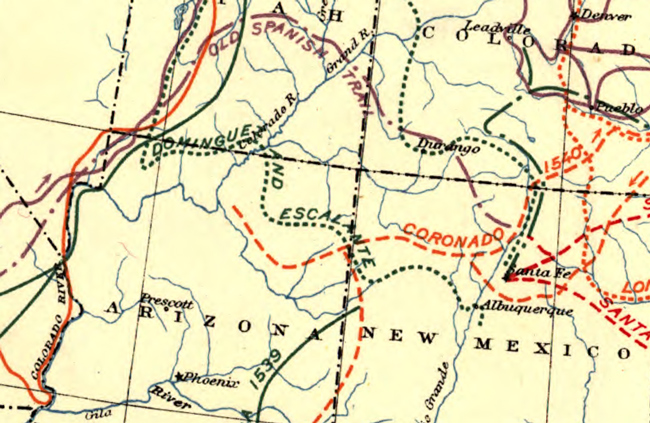

The earliest European maps described the Grand Canyon region as “parts unknown.” It almost seems as if explorers went out of their way to avoid Grand Canyon. In 1907, more than three-and-a-half centuries after Cárdenas first encountered Grand Canyon, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) produced a map “showing the routes of the principal explorers … whose work had an important bearing on the settlement of the country and the fixing of its successive boundaries.” Over hundreds of years, Cárdenas’ party (an offshoot of the Coronado expedition) is the only group to approach central Grand Canyon.

The map shows only a handful of routes that come anywhere near Grand Canyon. Most of these skirt the Colorado River near the present-day location of Lake Mead. The Dominguez-Escalante expedition is unique in that it covered land to the north of the Colorado River’s course through Grand Canyon.

In 1776, the same year that the American colonies declared their independence, the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition was mounted in attempt to discover an overland route between Spanish missions in New Mexico and California. The party left Santa Fe in July and initially traveled westward across lands far north of Grand Canyon.

After turning back that October in the face of the oncoming winter, the group traveled across northern Arizona, just south of the Utah border. Modern-day tourists roughly parallel Escalante’s route when they travel Highway 89A along the Vermillion Cliffs. However, the historic expedition never peered over the North Rim. Escalante’s diaries describe his desire to reach the Colorado River in northern Arizona, but he was warned by Native Americans that steep canyon walls would make it impossible.

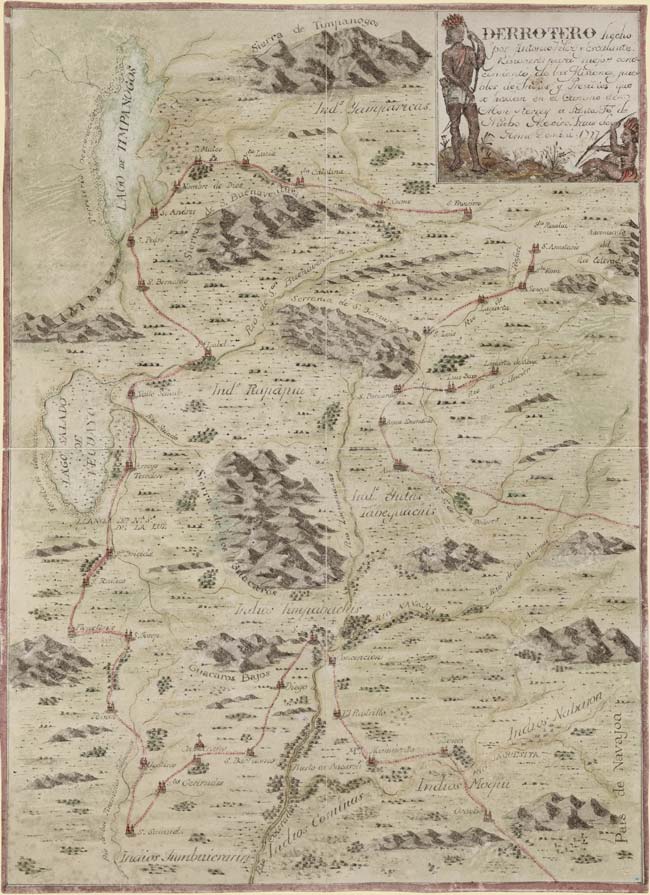

Although the expedition never saw saw Grand Canyon, it nevertheless produced maps depicting the Grand Canyon region. Escalante and the expedition cartographer, Don Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, created maps that generally agree with one another. Although neither presents the viewer with an obvious visual depiction of Grand Canyon, one of Miera’s maps describes the feature.

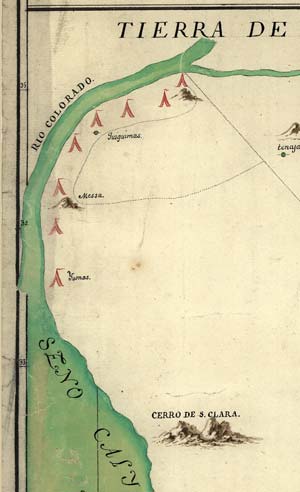

The confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers marks the end of Marble Canyon and the beginning of Grand Canyon, and is thus somewhat helpful for modern readers trying to understand these unfamiliar maps. Escalante refers to the Little Colorado River as the “Rio de las Coninas,” and Miera labels the Little Colorado River the “Rio Jaquesita.” Below is a comparison of one map from Escalante and one from Miera. In each map, the area occupied by Grand Canyon roughly corresponds to the area where the Colorado River is labeled.

In Escalante’s map, the area surrounding Grand Canyon is covered with little marks that appear to denote tree cover in the north and grasslands in the south. In the second map shown above, Miera has drawn something on the river’s north bank that looks vaguely like a mountain. Perhaps this is Mount Trumbull, a modestly sized volcano located in the present-day Arizona Strip. Although there’s nothing that visually resembles a canyon, Miera does make its presence very clear. An inscription shown in the lower left informs the reader that the Colorado River travels through steep, treeless canyons downstream of its confluence with the San Juan River. Miera is describing Marble Canyon and Grand Canyon:

“This Colorado River from the Junction of the two rivers of Saguganos and Navajo, tumbles down its canyons without trees, very much enclosed with colored rocks, and very deep and rugged.”

—Translation according to a 1941 paper

The original inscription is a bit hard to decipher, even if you speak Spanish. Miera refers to the San Juan River as the “Rio de Nabajo.” The Colorado River upstream of there is referred to as the “Rio de los Saguaganas.” In fact, Miera labels many of the rivers with names unfamiliar to modern-day readers. He conflates two Colorado River tributaries, the Green and Sevier, calling them the Buenaventura. For decades after Escalante’s expedition it was assumed to drain into the Pacific.

Escalante and Miera’s maps shown above also differ slightly in their location of “Indios Cosninas” (Escalante) and “Tierra de Coninas” (Miera). The two spellings are variants of a Spanish word “applied vaguely to Indians west of the Hopi.” Perhaps it’s no surprise that vague placements accompany vague appellations.

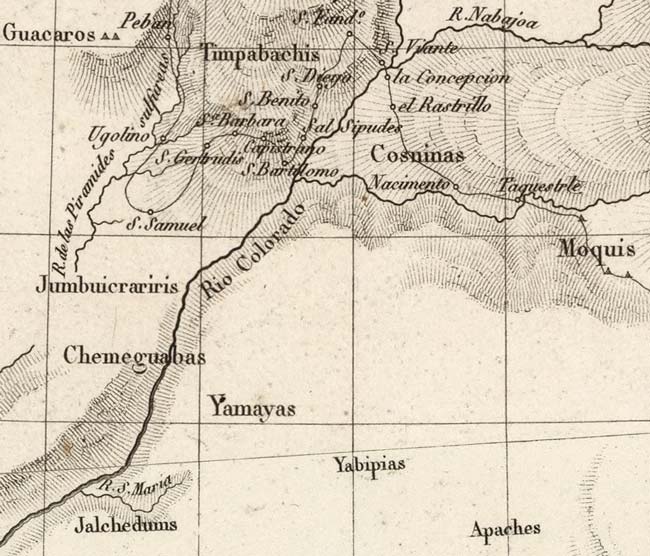

Miera’s maps were never published, but they were kept in manuscript form. They are thought to have informed the creation of later maps that depict what is today the southwestern United States. In 1803, Prussian naturalist and cartographer Baron Alexander von Humboldt visited Mexico City, where he examined Miera’s unpublished maps. The information he gleaned aided his creation of maps that were eventually published in 1811. Explorer Zebulon Pike is thought to have had access to that work-in-progress when Humboldt visited Washington, DC in 1804. Thus, Pike may also have been indirectly influenced by Miera. Maps produced by both men bear a strong resemblance to those from the Escalante expedition.

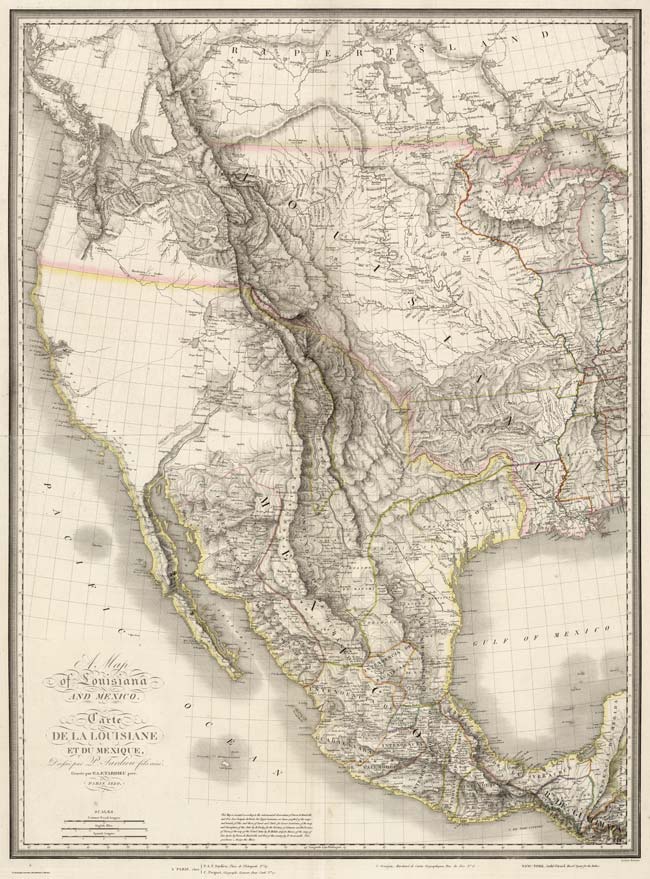

Escalante and Miera would continue to influence later cartographers through Humboldt’s work. French cartographer Pierre Antoine Tardieu explicitly credited Humboldt in a map published in 1820. Escalante and Miera’s influence is obvious in this map — their expedition route is depicted on the map, their cartographic errors are reproduced, and the region is marked with a simple proclamation: “Country seen by F. Escalante in 1777.” However, unlike Humboldt and Pike, Tardieu indicated the Colorado’s course through canyon country. For whatever reason, he places the most severe terrain along the present-day Arizona-California border — nevertheless, he records steep terrain around what we today know as the South Rim.

American trappers would make their first recorded visit to Grand Canyon in 1826, but it would be another several decades before American expeditions resulted in Grand Canyon maps far better than anything yet created. Part 2 of this post will examine the evolution of Grand Canyon maps from the Ives Expedition (1857) through the Matthes Survey (1903).

Thanks for the information. I’m staggered by these explorers resolve.

Thank you for the short but very informative history. I really enjoyed it. I also greatly appreciated the maps.

Thank you for the information. I love to learn about the history and exploration of our region!