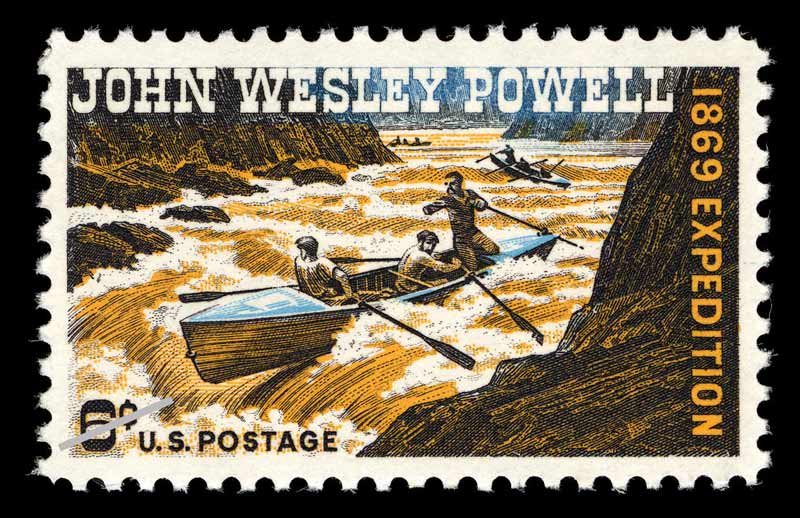

Lately I feel like a magnet for Grand Canyon ephemera. “Mike’s a hiking guide,” people say to themselves. “I should give all my old canyon junk to him.” That’s how I wound up with a postage stamp depicting John Wesley Powell’s 1869 descent through Grand Canyon.

I did a little digging, and I learned that the stamp was issued in 1969 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Powell’s expedition. The artist who designed the stamp was a Forest Service employee who drew and painted Smokey Bear between 1949 and 1973.1, 2

But as it turned out, I wasn’t content to know about just one Grand Canyon stamp. I had to learn about all the stamps. And a few canyon-related stamps have pretty interesting stories behind them.

Stampgate: A modest scandal from a simpler time

Leading the United States through the Great Depression was a stressful job, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt needed something to take the edge off. That something was stamp collecting.

FDR also had a buddy who was also into stamps: Postmaster General James Aloysius Farley.

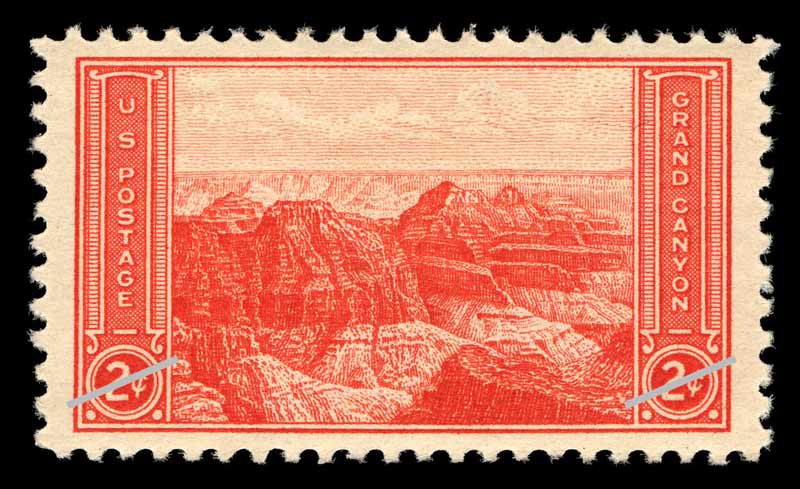

In 1934, during Farley’s tenure as Postmaster General, the US Post Office Department (USPOD, the precursor to today’s USPS) issued a series of stamps promoting various national parks.3 Ten different parks were given their own stamp, each with a specific denomination between one and ten cents. Grand Canyon was honored with a two-cent stamp.

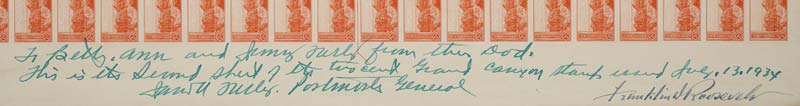

Farley had a habit of buying entire sheets of stamps right off the printing press, and he did this with all the national park stamps, Grand Canyon included. Typically, he would give the first sheet from a printing to FDR and save the second for his own family. Other sheets were given away to friends, cabinet members, and so on.5

Because the sheets Farley purchased came right off the printing press, they were ungummed and unperforated. “Ungummed” means they were never backed with adhesive. “Unperforated” means just that — they were never perforated. The New York Times inelegantly describes unperforated stamps as “lack[ing] those little holes to ease separation.”7

Being ungummed and unperforated, the sheets were extra-valuable. Stamp collectors were outraged to learn that the Postmaster General had special access to valuable stamps. There was an attempted Congressional investigation, and the National Postal Museum reports that Farley was “pilloried in both the philatelic and the popular press.”3

You know you’ve committed a very specific kind of high-profile offense when you’re pilloried in both the philatelic and the popular press.

Farley’s solution was to order the printing of enough ungummed and unperforated sheets to “satisfy collectors’ demand.” Motivated by a belief that the stamps were destined to increase in value, these reprints (Grand Canyon among them) were purchased in great quantities by collectors. But because so many were printed, their value was limited.7

These reprints became known as “Farley’s Follies,” and in 1935 they were responsible for the vast majority of commemorative and collector stamps sold by USPOD’s Philatelic Agency.8, 9 Annual revenue for the agency nearly tripled between 1934 and 1935.9

In fact, so many of Farley’s Follies were sold that the USPOD eventually offered to help dealers move inventory by gumming the ungummed stamps. That way the “collectible” stamps could at least be used as ordinary postage.7

Farley continued to attract controversy later in his career. According to the Chicago Tribune, a “leading philatelist” criticized a 1936-issue Susan B. Anthony stamp as “a political move to please the women voters of the nation.” If so, it was enormously successful: 200 million were sold.10

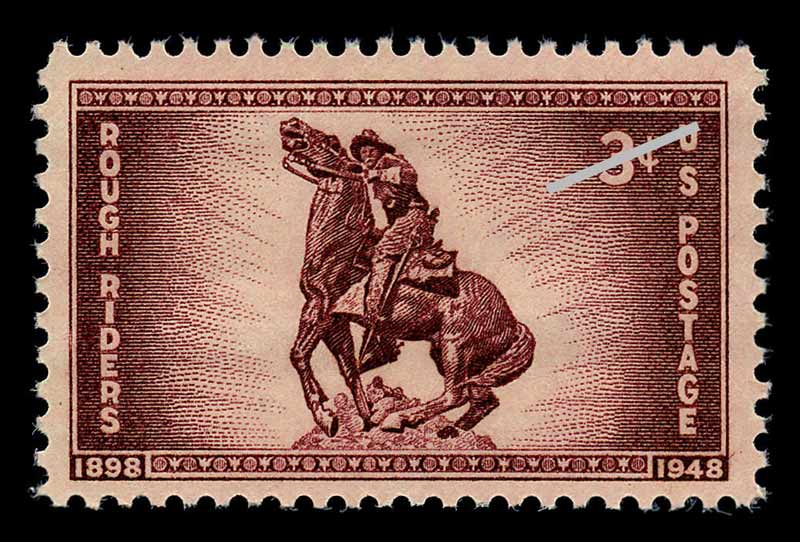

Rough Rider recognition results in risible rancor

William “Bucky” O’Neill is a minor historic figure whose name is pretty well known around Grand Canyon. There’s a picturesque butte named in his honor, and his cabin is the oldest standing structure on the South Rim. But O’Neill is best remembered for serving in the Rough Riders, a cavalry regiment that fought in the Spanish-American War under the leadership of Theodore Roosevelt. O’Neill died in the Battle of San Juan Hill in 1898.11

Fifty years later, Arizona Congressman Richard Harless introduced House Joint Resolution 305. It directed the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative stamp in honor of the Rough Riders, and specified that the stamp should depict a particular statue of Bucky O’Neill.12

The legislation passed, because who could possibly find fault with it?

Teddy Roosevelt fans, that who. The stamp attracted significant criticism from those who felt TR’s likeness would have been a better choice. “Theodore Roosevelt … whose name in the minds of the American people is forever synonymous with the very name ‘Rough Riders’ is entirely ignored in the stamp design,” wrote the editor of a philatelic magazine. Stirred by a sense of injustice, he continued his argument with a great pile-on of prepositional phrases. “Presidential election year or no, it ill benefits any American administration to thus deprive [a] great man of his heritage of memory among his countrymen of future generation.”14

Backwards Canyon, USA

My favorite story about Grand Canyon stamps is the one about the 60-cent airmail stamp. Its scheduled release in 1999 was delayed by complications.15

The stamp design was simple and straightforward. There was a scenic photograph, and there was a small caption: “Grand Canyon, Colorado.” This was in spite of the fact that Grand Canyon is located entirely within Arizona.16, 17

Unfortunately, the error was caught late in the production process. Really late. Like, after they were already printed late. Literally 100 million of these stamps had to be destroyed at a cost of $500,000.17

The caption was corrected, and a new version of the stamp was released on January 20, 2000. The occasion was marked with a ceremony that day in Grand Canyon National Park. But during the ceremony, someone familiar with the actual topography of the canyon noticed another error. The image had been flipped left to right.17

This wasn’t a newly introduced problem. The image had also been flipped in all of the 100 million destroyed stamps. When the USPS Office of the Inspector General investigated the erroneous caption in 1999, they overlooked (and even reprinted in their report) the backwards photo.18 In their defense, the design was already public, and no one else noticed it either.

Compounding this comedy of errors, The New York Times incorrectly reported that the flipped image depicts Lipan Point on the South Rim.19 The image appears to be shot from Lipan Point, and depicts landforms that appear on the North Rim.

With the stamps officially released, the USPS concluded that the error was not significant enough to warrant a reprinting. And so the canyon was left backwards, and life went on.16, 20

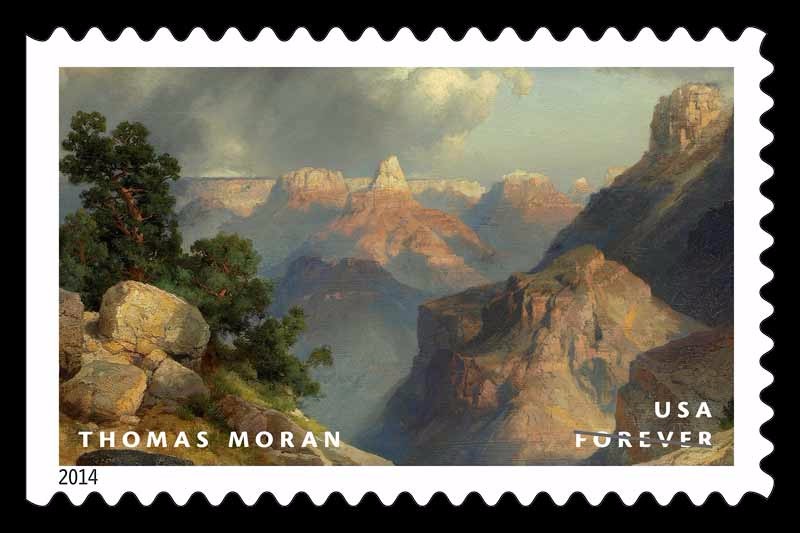

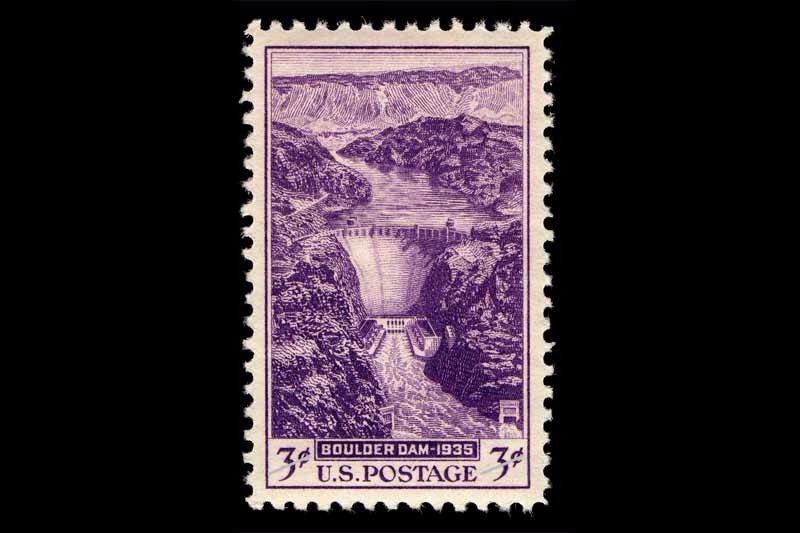

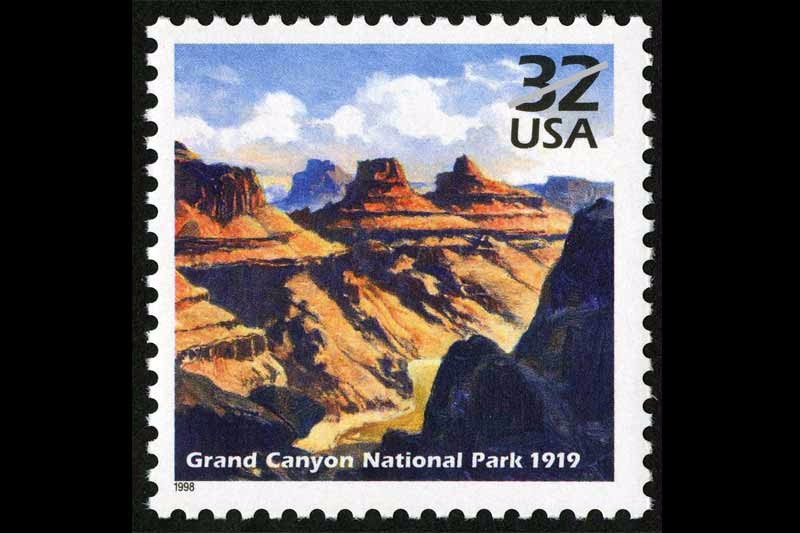

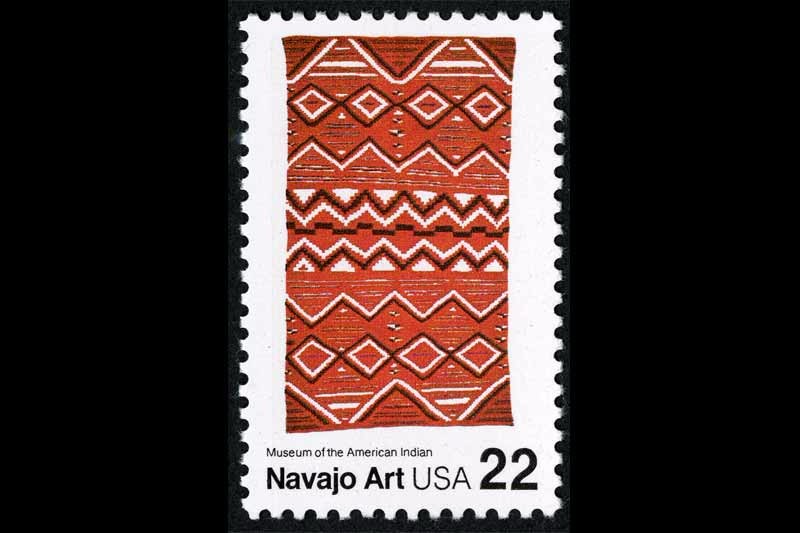

Above: A few more Grand Canyon (and canyon-related) stamps.

Great article, Mike! You never cease to amaze me with the incredible information you find. Thanks for sharing it.

Thanks, Denise! I did leave a couple interesting odds and ends out of the article. According to an obituary, Clarence Dutton was at one point very interested in stamps, and was even employed by the government “to make its Centennial stamp collection.”